TRIPTYCH.

Furniture - Object as Activist (2023)

Globalisation has led to an increasingly interconnected society; paradoxically, however, this has led to the erosion of local cultural identities (Giddens, 1990). TRIPTYCH addresses this very notion through a critical design lens, that is, utilising design as a medium to critique contemporary issues. It also utilises design anthropology to strengthen these critiques, drawing upon theoretical and cultural interpretations from anthropology (Gunn et all, 2013); this is closely linked to material culture theory, which studies an object’s significance by examining factors such as materiality, style, making techniques and textual accounts (Prown, 1982). These factors form the foundation of TRIPTYCH, articulating third space theory, which posits that each person is a product of their hybrid and unique affinities such as class, location, kin, etc (Bhabha, 2004).

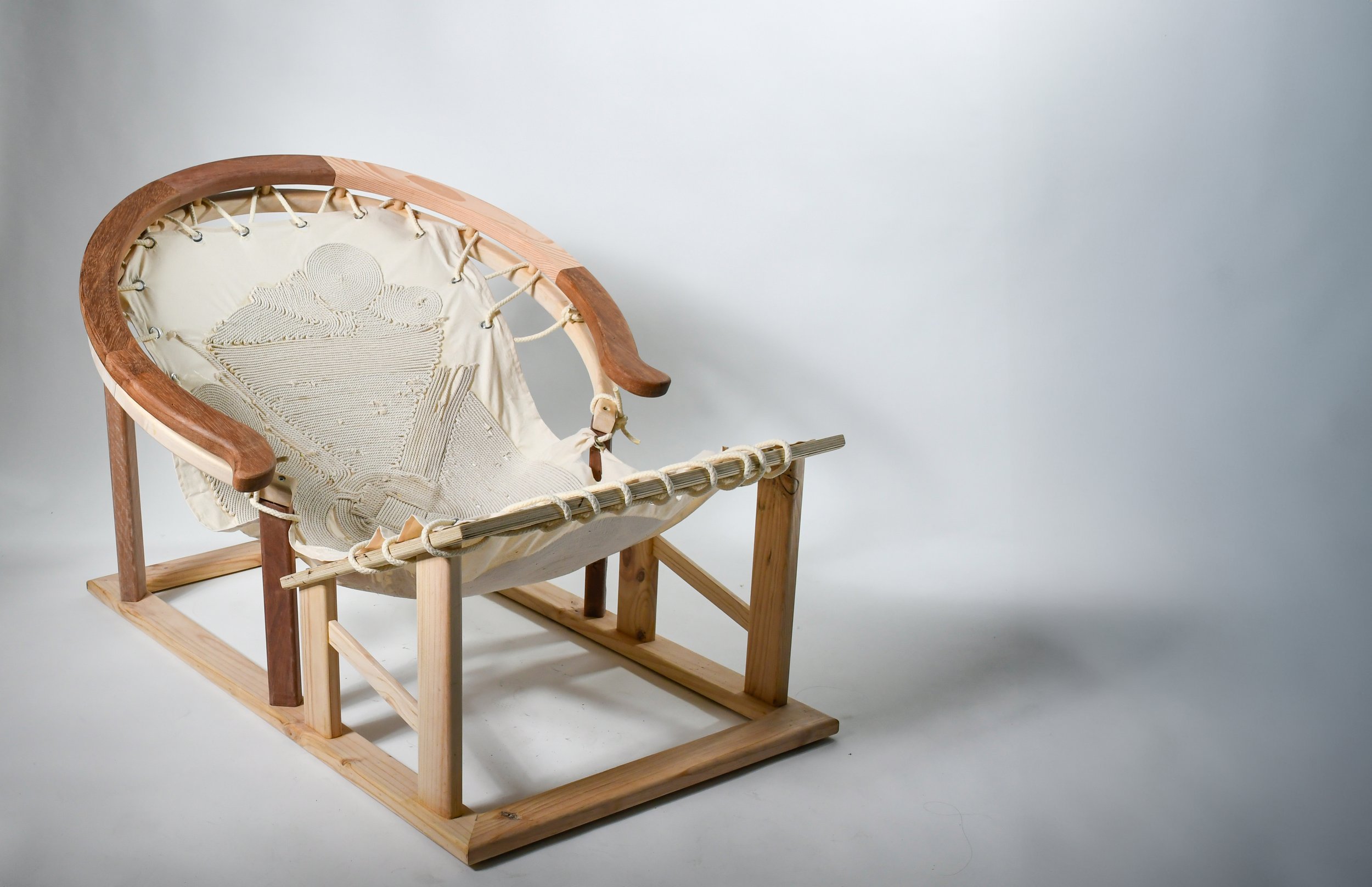

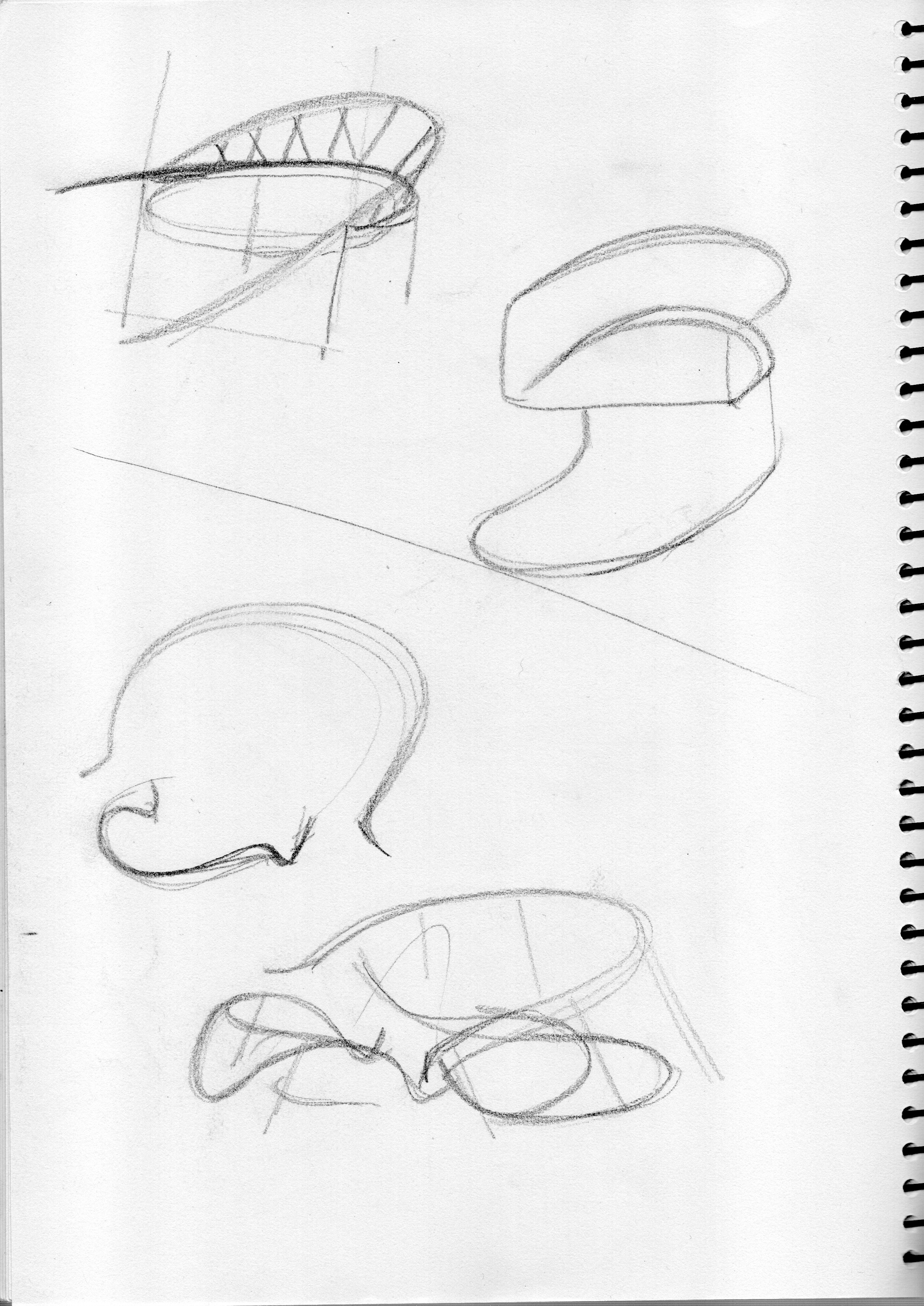

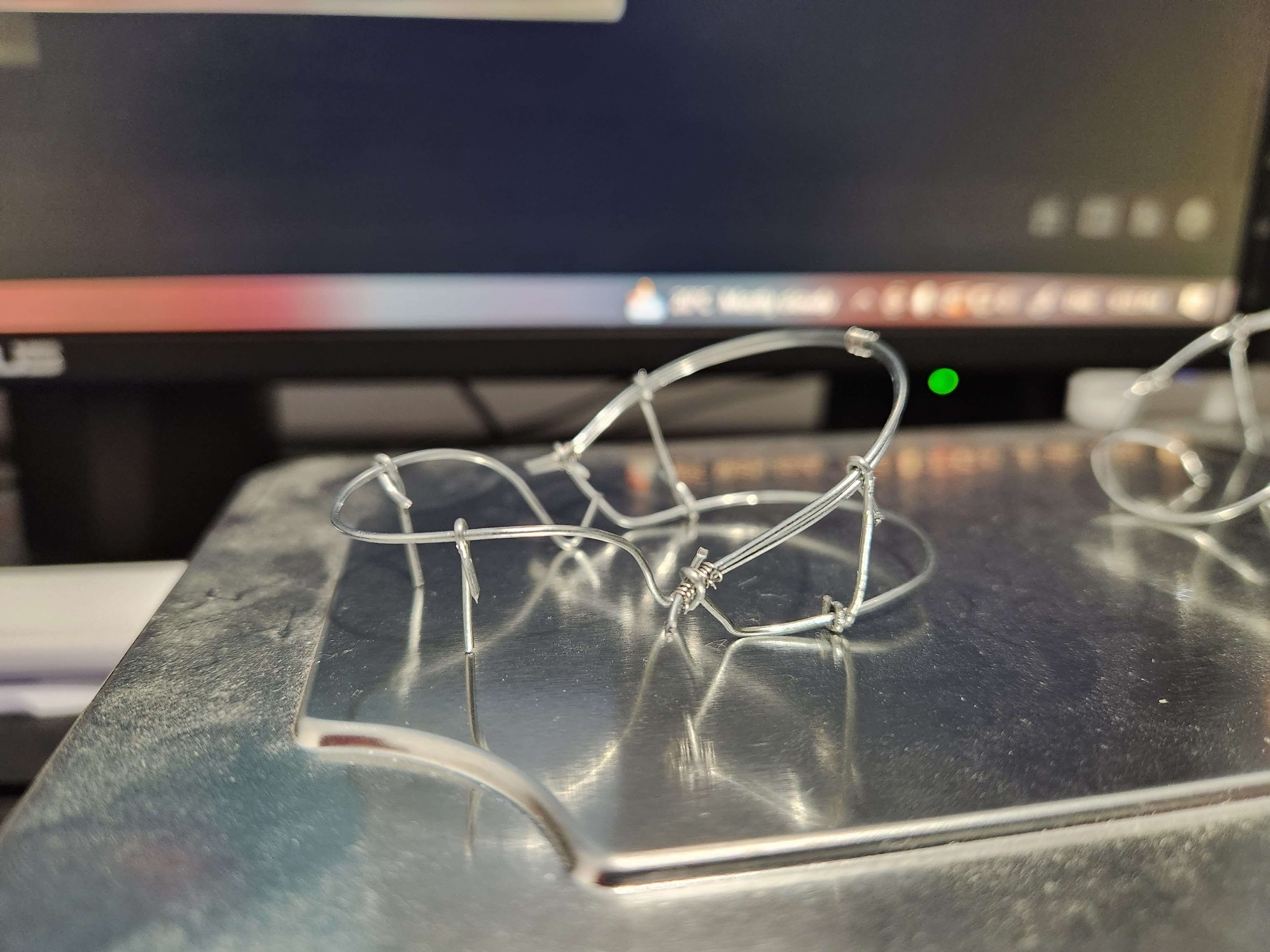

TRIPTYCH takes two iconic chairs which personify being Chinese and Australian respectively and marries them into one. The Quanyi Chair, for instance, is a traditional Chinese chair which illustrates the Chinese affinity for manners and discipline through its straight wooden backing. The ancient Chinese proverb, “行如風, 立如松, 坐如鐘, 臥如弓” further supports this (Lu, 2014). Directly translated, it means “walk like a breeze, stand like a pine, sit like a bell and lie like a bow,” alluding to expectations on posture and mannerisms. Conversely, the iconic Australian foldable beach with its hammock-like woven seating personifies the Australians’ laid-back way of life and their tendency to put aside stress to enjoy the good things in life (Australia, n.d.) By synthesising the two, TRIPTYCH celebrates cultural hybridity and intersectionality.

TRIPTYCH’s chair frame is inspired by the Quanyi Chair’s circular backing and represents the ever-evolving nature of cultural identity. A square frame is juxtaposed against this, representing the innate tendency to oversimplify and catalogue cultural identities into preconceived ideas of what one’s cultural identity should be (Ferenczi, 2014). The seating spans across these two frames, literally bridging the gap between them and suggesting an alternative where cultural hybridity is celebrated. The seat’s patterning is one which reimagines the Chinese button knot to represent the uniqueness of cultural identity. At the centre of the seat is part of the basic button knot -a traditional Chinese knot consisting of layers of cord criss-crossed over each other- to signify the importance of holding onto out cultural roots. The knot then branches out to form a randomised pattern consisting of layers upon layers of cord, illustrating the nuances and richness of identity. It also references the non-linear journey one takes in reconciling their cultural identity and how different life experiences - represented by the circular forms which interrupt the flow of these free-flowing strands- impact how we form our personal cultural identity. It therefore celebrates cultural identity as something that is constantly evolving and shaped through culminations of lived experiences and worldviews. Therefore, when someone sits in TRIPTYCH, they are sitting in the third space that bridges the two opposing frames.

Australia. (n.d.). A HANDY GUIDE TO THE AUSTRALIAN LIFESTYLE. https://www.australia.com/en/facts-and-planning/about-australia/the-aussie-way-of-life.html

Bhabha, H. K. (2004). The location of culture. Taylor & Francis Group.

Ferenczi, N., & Marshall, T. C. (2016). Meeting the expectations of your heritage culture: Links between attachment orientations, intragroup marginalization and psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(1), 101-121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514562565

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Polity Press.

Gunn, W., Otto, T., & Smith, R. C. (2013). Design anthropology : theory and practice. Bloomsbury.

Lu, Y. (2014). Breaking bad posture. The Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/846138.shtml#:~:text=An%20ancient%20Chinese%20proverb%20about,on%20traditional%20Chinese%20medicine%20theory.\

Prown, J. D. (1982). Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method. Winterthur Portfolio, 17(1), 1–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1180761